Mubashar Hasan

Both the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party have Islamist allies and wear their religious identity with pride.

Bangladesh will vote in general elections on January 7. International media coverage has focused on the Awami League (AL)’s slide toward authoritarian rule and doubts over whether elections held under the regime will be free and fair. The opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which is calling for elections under a neutral caretaker government, has threatened to boycott the elections.

The foreign media has tended to frame the AL-BNP contest as one between secular and Islamist forces, with the AL being perceived as a secular party and the BNP as a conservative one.

A major reason for the perception of the AL as a secular party is that following the independence of the country in 1971, the AL government endorsed secularism as one of the key state principles. Historical documents and policy analysis reveal that there was indeed a faction within the AL that truly believed in the strict separation of religion from the state and was inspired by socialist-communist ideologues. Over the decades, most of Bangladesh’s socially progressive forces have also aligned with the AL. Some experts have also argued that AL’s founding ideology of Bengali nationalism and its ethno-linguistic connotations have further strengthened the perception of the party as a secular one.

As for the perception of the BNP as a conservative party, this is largely because it has had ties with Islamist parties like the Jamaat-e-Islami.

A closer look at Bangladeshi politics reveals that the religious/secular orientation of the main parties is not in fact that clear-cut.

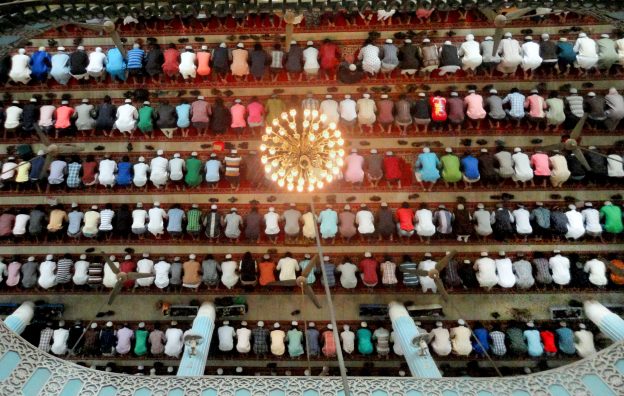

A predominantly Muslim country, Bangladeshi society and politics are deeply infused with Islamic religious values, with both the major parties, the ruling AL and the opposition BNP, drawing on religion to appeal to the masses.

To understand the current nature of secularism in Bangladesh it is useful to understand it through the prism of the liberal interpretation of Islam, which means Bangladesh’s rulers consider secularism to be a part of an Islam that supports freedom of religion for all.

When the AL brought secularism back into the Bangladeshi constitution in 2010, it also retained Islam as the state religion. As Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who is also AL chairperson, said “Bangladesh will be run as per the Charter of Medina, where people from all religions will practice their own religion in a festive mood.” This has opened space for interpretation that to the ruling Bangladeshi elites, secularism could be inspired by Islam.

While the BNP has been persistently vilified for its ties with the Islamists, the “secular” AL too has Islamist allies. In fact, before the 2018 election, out of 70 active Islamist parties, 61 were associated with the AL or its electoral alliance.

Besides, there is no visible difference between the way AL and BNP promote religion in state policies and party platforms i.e., its election manifestoes and speeches.

For example, the AL’s constitution prominently displays the words Allah Shorbo Shaktiman (Allah is the most powerful) on its cover, underscoring the significance of Allah to the party.

Bangladesh’s founding father and first President Sheikh Mujibur Rehman and his family — the current prime minister Sheikh Hasina is his daughter — may have publicly championed religious harmony and freedom but they also never shied away from displaying their Islamic identity.

Perhaps, this was among the reasons why immediately following independence, Bangladesh saw the emergence of the radical leftist party Jatiyo Samaj Tantrik Dal, which was keen to challenge Rehman’s vision of secularism with what they claimed as “scientific socialism” for the country.

Under Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s government (1972-1975), Bangladesh was a secular state. Yet many policies pursued by the government upheld Islamic cultural values in state affairs. For example, it banned gambling and selling of alcohol in the country, and closed cinema halls on the Prophet’s birthday. It established an organization that was the forerunner of the Islamic Foundation, a state-funded Islamic missionary organization, and reformed the Madrasah education board. In 1974, Bangladesh poet Daud Haider was forced out of the country for offending religious sentiments through one of his poems.

Moreover, in 1974, at a summit of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC), Mujibur said that “75 million people of Bangladesh were fully committed to contributing in every way possible to the success of Muslim ummah” and he hoped that “almighty Allah would crown the collective endeavor with success.” In that summit, he proposed a new international Islamic order to challenge the domination of the West.

Some would argue that AL’s inclusion of secularism in the constitution was a rhetorical construction rather than a reflection of an ideological standpoint. Its antagonism to the Jamaat-e-Islami is a manifestation of a strategic move, not the outcome of any belief in secular principles.

The BNP too followed the strategy of upholding Islamic culture and values in state affairs. However, unlike the AL, it removed secularism from the constitution and replaced it with the words “absolute trust and faith in almighty Allah.” This was useful for the party to secure the support of the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries where Bangladesh started sending its unskilled and low-skilled laborers for employment.

In its election manifestos of 1991, 1996, 2001, and 2008, the BNP explicitly mentioned that it would protect Islam’s honor and that Islam would be its guiding principle in politics, and therefore, people should vote for the party to “save and protect Islam.”

Religion continues to infuse state affairs. Since the late 1970s, state investment in religious affairs has grown by over 6500 percent. AL and BNP governments as well as those backed by the military have maintained this strategy.

In my book “Islam and Politics in Bangladesh: The Followers of Ummah” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020) I pointed out that Bangladesh’s mainstream politicians across the political divide stress their Muslim identity. They do not hold back from infusing religious culture into state and party affairs and see Bangladesh as part of the Ummah or global brotherhood of Muslims. That is why Bangladesh’s cooperation with the OIC has grown over the decades.

A country that sees itself as part of a global collective of Muslim states will be highly critical of atheism. Consequently, hurting “religious sentiment” has been made a criminal offense in Bangladesh despite objections from secular forces in the country. To display atheist beliefs is risky in Bangladesh today.

Both parties have also publicly said Islam is a religion of peace and they do not encourage violence in the name of Islam despite associating with Islamist parties on numerous occasions.

This article was first published on The Diplomat, on November 16, 2023