Jyoti Rahman

Shaon Prodhan, Shahidul Islam Shaon, Nayan Mia, Maqbul Hossain and others like them were working class and self-employed young men in Bangladesh – rickshaw pullers, vegetable vendors, welders, factory workers, tailors, and so on. They risked violence from the ruling Awami League workers and law enforcement agencies to attend rallies and meetings of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) – the country’s main opposition party. And they paid the ultimate price for participating in overwhelmingly peaceful protests against inflation, crippling power shortages, and the right to vote in a free and fair election.

These protests have become more frequent in the past year and the government’s reprisals more brutal. They signify a few facts about Bangladesh that need to be better understood in India.

Firstly, Bangladesh’s economy is not delivering for its people. That the economy is in trouble is self-evident – no one takes a nearly $5 billion loan from the IMF otherwise. Inflation is running at nearly double digits by official count, but in reality is perhaps much higher because the authorities are known to fudge the data. Meanwhile, the government seems to be unable to pay for imported coal to fire up power plants, leaving people without electricity for hours on end in the middle of summer.

The official explanation for the economic woes is the war in Ukraine. But the economic malaise, in fact, has causes that run much deeper. After the precarious, war‑ravaged, famine‑stricken early years, Bangladesh’s remarkable economic transformation over the past few decades – on the back of rising female literacy and employment in the ready-made garment sector and remittances from Bangladeshis working abroad – is now well understood. In India, news reports have pointed out that on average, Bangladeshis might now earn more than the average Indian. But what is left unsaid is the fact that even according to the Bangladesh government’s own measures, inequality has widened over the past decade, with the Gini coefficient (an index for the degree of inequality in the distribution of income/wealth) rising from 0.46 in 2010 to 0.5 in 2022.

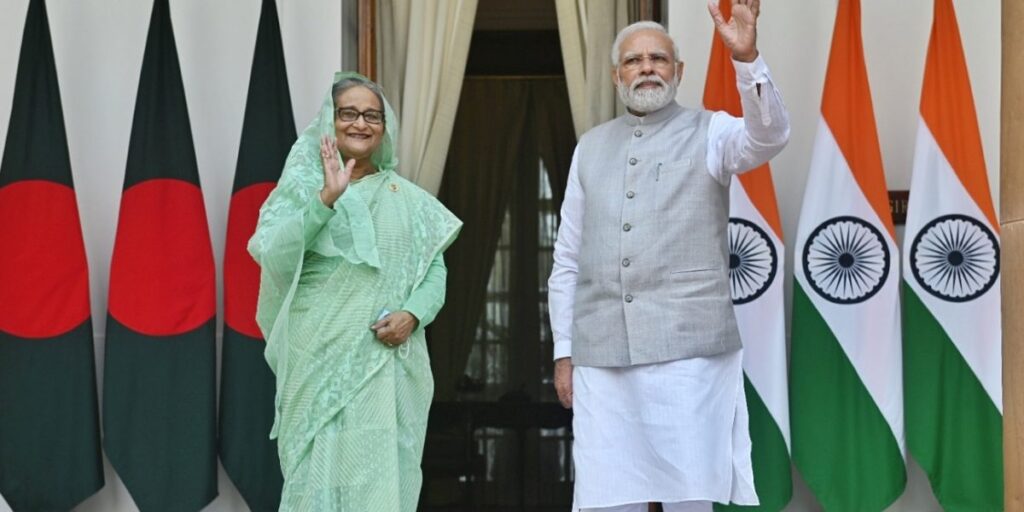

And this rising inequality is not a bug, but a feature of the Sheikh Hasina government that has been in power since 2009. Instead of continuing the policies of previous governments (including her own in the late 1990s), the Hasina regime took a very different route in the 2010s. It struck a deal with the country’s emerging business tycoons whereby, in exchange for helping the prime minister rig elections, the oligarchs would be given access to infrastructure mega-projects and other business opportunities without oversight.

Take electricity, for example. Power purchasing agreements with not just local businessmen but also the Indian Adani Group were signed with terms and conditions that allowed the power suppliers to take an enormous cut of the total project price. And parliament passed a law prohibiting anyone from investigating the matter.

Political cronies were allowed to set up banks without proper governance frameworks. Attempts were made to steal nearly a billion dollars from the country’s foreign exchange reserves in a caper worthy of a Hollywood movie in 2016, but the investigation report on the case is yet to be made public.

While the regime has prioritised mega-infrastructure deals like the comically one-sided coal‑fuelled power plant deal with the Adani Group, or the $7.1 billion infrastructure loan inked with China, Bangladesh’s public expenditure on education and health is far lower than many of its neighbours. It is the government’s priorities that are driving the economic woes.

When the global economic conditions were favourable, the country’s working poor still saw incomes rising. Income now is falling behind the cost of living. No wonder then that the working poor are despondent and protesting.

Bangladesh’s much-vaunted development success story is at the risk of coming undone. However, contrary to the fear of many progressive and liberal Indians, the threat to development is not coming from Islamic fundamentalists and extremists opposed to female empowerment and social transformation.

It is the Hasina government’s economic model that is putting the country’s development at risk – the second fact about Bangladesh that needs to be understood.

The BNP’s history of reform

The third, related, fact is that the protesters are not flocking to Islamic fundamentalists, extremists, militants or populist peddlers of communal-sectarian-ethnic hatred. They are risking police firing to attend rallies and meetings of a political party that is avowedly moderate, and cautious in its policy platform and political message alike.

Contrary to the propaganda coming from the acolytes of the Hasina regime and their supporters in India, the BNP has always been a party of democratic reform and pragmatic development policies.

In its first term in office in the late 1970s, the party ended martial law and the one-party system that was introduced by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. In its second term in the 1990s, the BNP amended the constitution to restore the parliamentary system and introduce an election-time non-partisan caretaker government.

In 2008, the party put the restoration of democracy in the country ahead of its narrower partisan interests and contested an election that it knew it would lose. The playing field was less-than-level, with the then quasi-military regime targeting its rank and file over the previous year in a failed attempt to create a ‘King’s party’.

On the economic front, the garments industry, migrant workers, and female empowerment – factors that drove Bangladesh’s development in the past few decades – were all results of policies by successive BNP governments.

Against the backdrop of economic hardship and simmering discontent against the regime, BNP’s message harkens to that track record of democratic renewal and pragmatic developmentalism. Crucially, it promises a national government which, after the election, will ensure lasting institutional reforms to restore democracy.

Of course, that promise assumes that there will be a free and fair election. The last two elections, held under Hasina, were anything but that. In January 2014, more than half the MPs were elected unopposed, giving the prime minister a parliamentary majority without a single vote being cast. In December 2018, to ensure victory, Awami League cadres and its cronies in the civil administration and law enforcement agencies stuffed the ballot boxes the night before the election.

This brings us to the fourth fact: Hasina must step down if Bangladesh is to avoid certain disaster. The idea that there can be a free and fair election under her is a case of twice bitten, thrice shy. A non-partisan caretaker administration is an absolute must for a free and fair election in Bangladesh, and only a democratically elected government can restore economic stability. If the democratic avenue is thwarted, simmering discontent will have no alternative but to boil over.

India has a choice to make

Great powers appear to understand the situation in Bangladesh very well. The Joe Biden administration in the US does not want a potential development success story to become yet another economically stagnant dictatorship, and therefore has announced a new policy that will deny visas to anyone partaking in election rigging. China senses an opportunity to court a potentate in the Hasina regime.

For obvious historical reasons, of course, India has a special relationship with Bangladesh. No other country will be affected as much as India if Bangladesh’s careen towards a crisis continues. If India were to stand behind the Hasina regime till the bitter end, it would just exacerbate the situation, not resolve it. More importantly, this would only fuel anti-Indian sentiment in Bangladesh, to be exploited by some future populist demagogue.

On the other hand, if India were to take a firm stance on helping restore democracy in Bangladesh, it would likely find a willing partner in the BNP. Contrary to the perception, the opposition party is not inherently anti-Indian, and previous BNP governments had worked amicably with India. For example, successive BNP governments adhered to the India-Bangladesh 25 Year Friendship Agreement that was signed by the two countries’ prime ministers in 1972.

Therefore, either from a cold hard realpolitik perspective or to keep faith in its cherished democratic ideals, the facts laid out above should make India choose democracy in Bangladesh.

A free and fair election would be the most effective way for the country to avert a deeper crisis. Parliamentary elections are due in the winter of 2023-24. Before that, however, there are several more months of heat, monsoon, and the late autumn cyclone season. The people of Bangladesh have lived with monsoon floods and tropical storms since time immemorial. As the Assamese singer Bhupen Hazarika sang in an iconic movie about the Bhola cyclone of 1970, ‘jhoro hawa bhenge diyo, miththe tasher ghor’ (the gale will blow away the false house of cards).

A storm is brewing over the Bengal delta. It’s not too late to avoid calamities.

This article was first published on The Wire, on 21 June 2023